[ad_1]

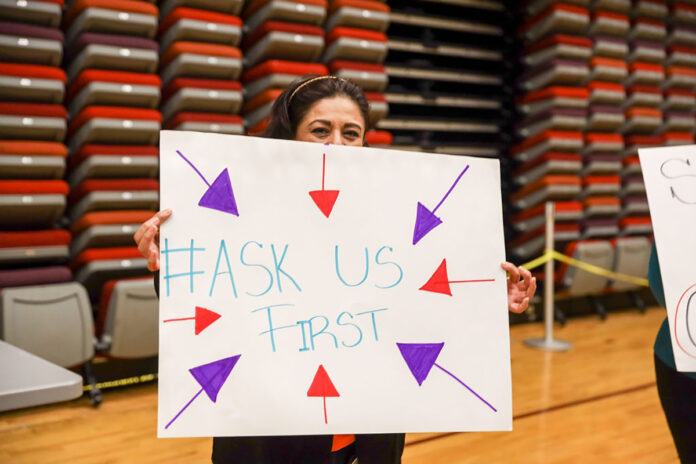

A parent, parent leader, and community representative on Back of the Yards College Prep’s Local School Council, Consuelo Martinez de Ferrer knows a lot about Chicago’s public schools. Like many others who closely watched the city’s recent school board elections, she sees the results as a mixed bag. Speaking in Spanish, she described the results as “un poco bien,” or kind of good, citing high turnout and voters’ persistence through the ballot.

But she and many others are disappointed that the first-ever election didn’t bring ordinary parents like her into board seats. Although four parents of current students won seats, three of them were supported by moneyed interest groups and one is a former Chicago Public Schools (CPS) principal.

“As the mother of a girl with a disability, I would like there to be seats for parents who know how the day-to-day is in the schools and what the system should do to improve children’s classroom experiences,” she said.

Candidate Adam Parrott-Sheffer, who lost his bid for the District 10 seat, agrees that this election didn’t deliver true grassroots governance. “If the goal of this was to have the folks closest to our schools have greater voice . . . there’s work to do.”

For ordinary parents wanting to run for school board, this inaugural election involved some big obstacles. First came the 1,000-signature requirement to get on the ballot. (For comparison, someone running for City Council only needs to gather 473 signatures.) Then those signatures had to survive the arcane challenge process, which experienced Illinois politicos have long used to ice out rivals. Finally, running a successful campaign proved to be expensive. A recent analysis by Kids First Chicago, a parent advocacy group, showed that the school board election winners spent at least $50,000 on their campaigns.

These realities, plus campaign mudslinging and misinformation, suggest that disillusioned voters could have chosen to skip voting in these races. Remarkably, they didn’t. An impressive number of Chicagoans voted in the school board election: about 78 percent of those who cast ballots on November 5 chose a candidate in school board races, more than the share who voted in all but one of the judicial races. Also, the results did not produce a clear victory for any one interest group. The winners included four Chicago Teachers Union–endorsed candidates, three school-choice supporters backed by groups opposed to the CTU, and three independent candidates.

Interim school board stumbles, yet they may stay on

Meanwhile, Mayor Johnson’s interim board, appointed on October 24, has struggled to find its footing. Board President Mitchell L. Ikenna Johnson resigned at the end of his first week in office after offensive social media posts of his resurfaced. So far his seat has yet to be filled. It seems unlikely Mayor Johnson will fill the vacancy until he announces his full slate of appointments to join the elected members to be seated in January.

Although December 16 is the deadline to announce those appointments, the mayor’s office has already told WBEZ that he would like the six remaining members of the current interim board to stay on. Based on the election results, they could. Five of the six live on opposite sides of the district from elected members, which allows them to be appointed under the state law that created the transition process to a fully elected board. The sixth current board member, vice president Mary Russell Gardner, could stay on if Mayor Johnson appoints her to the board presidency, since the board president can live anywhere in the city.

Speculation about who the remaining five appointments might be has centered on three CTU-backed candidates who lost their races, but Kids First Chicago and allied community groups are asking the mayor to appoint more parents and more people from racial and ethnic groups representative of the CPS student body.

“We should have more Latino parents on the board, more Black parents, at least one Asian parent,” observed Martinez de Ferrer, who also serves on the Kids First Elected School Board Task Force.

Regardless of who Johnson chooses, his 11 appointees plus the four CTU-backed elected board members theoretically equal a supermajority on the incoming board for the mayor and his close union ally. But in practice, matters may be more complicated. “Even if there is a majority interest, it’s going to be harder to get there than anybody can assume at this point,” District 2 winner Ebony DeBerry, who was endorsed by the teachers union, told WBEZ’s Reset.

Meanwhile, the interim board has yet to move on two closely watched mayoral priorities: approving a $300 million short-term loan to help plug this year’s budget deficit and removing CPS CEO Pedro Martinez from his position. Both proposals are politically unpopular with both the City Council and many ordinary Chicagoans, including CPS parents like Martinez de Ferrer.

While talk of taking out the $300 million loan has receded due to political pushback, the effort to fire Martinez may still be underway. The board called a special meeting on November 14 that included a long closed session to discuss personnel matters. Four days later, union president Stacy Davis Gates sent Mayor Johnson a letter accusing Martinez of “slow-walking” negotiations and urging the mayor to “direct” the board to take “bold action” to settle the contract. The board is not scheduled to meet again until December 4, when it will set the agenda for its regular meeting on December 12. But it could call a special meeting any time, as it has already done.

All this comes on top of the appointment of a neutral fact finder who will evaluate the district’s finances and analyze how they would be affected by the contract proposals now in talks. This is one step toward a teacher strike, but the process to approve a strike would take until February at the soonest.

Could better training and a new vision for governance help? Maybe.

How successfully the incoming mix of elected and appointed school board members could navigate these choppy waters come January depends in part on the quality of training they receive. Angel Gutierrez, newly elected board member for District 8, wants to see the board focus on big-picture governance and a carefully chosen set of priorities. “We need to be doing strategy,” he said. “I want us to focus on five big things,” and rattled off four on his mind already: finances, academics, special education, and facilities.

District 3 board member Carlos Rivas got a taste of what high-quality board training could look like by participating in the first Academy for Local Leadership (ALL) cohort at National Louis University, a new program created to help ordinary Chicagoans prepare to serve as education leaders, including as school board members. Rivas was the first ALL fellow to win a school board seat. “It wasn’t focused so much on the politics of running but much more on the politics of governing.”

“I learned it’s really about how to build consensus among the 21 members,” Rivas said. “For the school board, it’s thinking about what’s good for the whole district, not just for the schools I represent.” This is especially important because CPS families send their children to schools all over the city, especially when they reach high school.

Bridget Lee, who leads the ALL program, expressed cautious optimism about the elected members and the future of the fledgling board. “I have a good feeling about the people going in,” she said. “I’m just hopeful they’re able to focus on their responsibilities, not on rhetoric that happens when you’re campaigning but doesn’t need to be carried over into governing.”

She’s also hopeful that the new board can shift its work away from a traditional scope of approving staff decisions and managing for legal compliance toward a more strategic vision for school improvement. “Historically, the board spent most of its time talking about how things are being managed. There was not a lot of time for talking about young people and their experiences,” she noted. “But this board can change that.”

Improving the campaign process

While the political and financial drama surrounding the school district continues to unfold, grassroots parents and community leaders are already analyzing how to improve the campaign and electoral processes to give ordinary people, especially parents, greater representation.

The biggest challenge on the table–as it is for all U.S. elections–is how to reduce the influence of money in the school board races and ensure less-resourced candidates have a fair shot at becoming known to the public. In mid-November, Chalkbeat Chicago reported that more than $9 million was spent on the school board races, including independent expenditures by interest groups that did not coordinate directly with candidates’ campaigns.

At a late October press conference, northwest-side state senator Robert Martwick and other state lawmakers pledged to limit future campaign spending, but exactly how that would happen remains to be worked out. Kids First Chicago has advocated for strict spending limits, but the Supreme Court’s decision in the Citizens United case makes it impossible to limit the spending of independent groups, or “super PACs,” which accounted for about $4 million of the money spent to influence voters’ support of school board candidates.

On November 23, the progressive organizing group the People’s Lobby hosted a town hall on reforming Chicago’s municipal elections by creating a public fund to match small-dollar contributions to grassroots candidates. Already, 26 cities and 14 states have adopted variations of this idea. “Some kind of public finance match would be helpful in leveling the playing field,” said Grace Chan McKibben, executive director of the Coalition for a Better Chinese Community and former communications director with Common Cause Illinois, a leader in the fight for fair elections. “I know that it’s going to be an uphill battle. We’re already not balancing the [city] budget. Asking for something like a campaign finance fund would be difficult, but we think it’s important.”

It is possible that two other problems–the petition signature challenge process and incorrect ballots handed out in precincts split between school board districts–combined to deny candidate Karin Norington-Reaves a victory in the 10th District. In mid-August, candidates Robert Jones and Che “Rhymefest” Smith dropped their petition signature challenges against each other. Norington-Reaves said the mutual agreement to drop the challenges occurred when both Jones and Smith were found to have slightly less than 1,000 valid signatures. With the challenges dropped, both could stay on the ballot despite failing to meet the valid signature requirement. Norington-Reaves said her signatures were also challenged, but she successfully defended them.

Then, on Election Day, a number of voters in District 10 were given ballots listing school board candidates for the adjacent Districts 9 and 6—not for 10. This happened most frequently in precincts that were split between school board districts. Norington-Reaves and her lawyer are continuing to investigate what happened.

“I find all this so disheartening. Somebody who should not have been on the ballot won,” said Norington-Reaves. “It’s a hot mess, and you can’t rectify this except by a special election, which I know they won’t do. The most important thing is that these things get remedied so this doesn’t happen again.” The final election results, which were to be certified by the Chicago Board of Elections as this article went to press, showed Smith winning the four-way race with 25,922 votes, or 32.21 percent, and Norington-Reaves coming in second, with 23,543 votes, or 29.25 percent.

In an interview, fellow District 10 candidate Parrott-Sheffer suggested technology could be used to verify signatures and eliminate the challenge process. Norington-Reaves suggested color-coding ballots in precincts where more than one school board race is in play.

Local schools need you now more than ever

Just because the school board election is over doesn’t mean it’s time for Chicagoans to take a step back from their local schools. The national election results could have implications for CPS, even though the federal role in education is quite small. For example, president-elect Donald Trump’s campaign promise to deport millions of undocumented immigrants nationally could potentially affect thousands of CPS students and families. “When the world is going to shit, the most important things to do are the most local,” said Parrott-Sheffer.

That could mean filling a vacancy on a Local School Council. “I think it’s always a good time to get involved with your Local School Council,” said Bridget Lee. “People being more invested in democracy and more civic-minded could be a way to prepare ourselves to organize and build coalitions” to defend against federal efforts to undermine Chicago.

“The interests of the students must be protected,” said Martinez de Ferrer. “And who better [to do that] than parents and teachers who have been close to classrooms and know what students really need.”

[ad_2]

Source link